Image Type

Segmental Lordosis

1) Description of Measurement

Segmental Lordosis quantifies the curvature of a defined lumbar motion segment, typically measured between two adjacent vertebrae (e.g., L4–S1 or L1–L5).

It represents the localized sagittal alignment of the lumbar spine, providing detailed information on curvature distribution, segmental compensation, and regional contribution to overall lumbar lordosis.

This measurement is especially important for assessing:

Postoperative fusion angles

Disc space collapse or restoration

Segmental contribution to global sagittal balance

2) Instructions to Measure

Obtain a standing lateral lumbar spine X-ray, ensuring inclusion of the segment(s) of interest (e.g., L4 through S1).

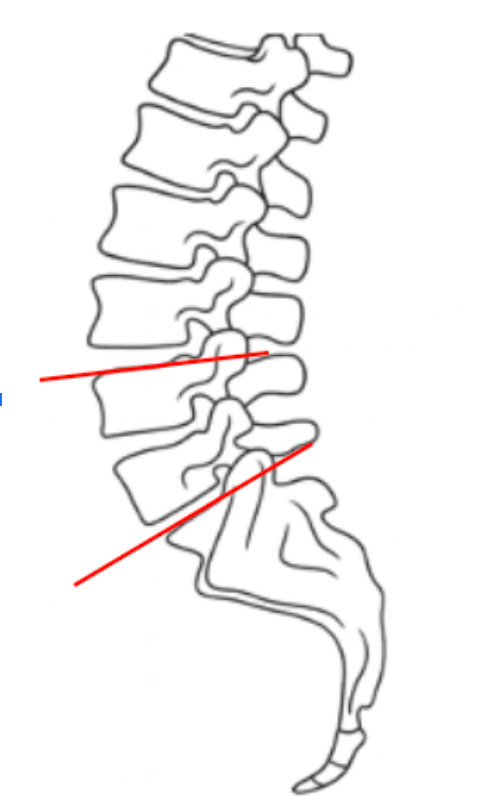

Identify the superior endplate of the upper vertebra (e.g., L4) and the inferior endplate of the lower vertebra (e.g., S1).

Draw a straight line along the superior endplate of the upper vertebra.

Draw another line along the inferior endplate of the lower vertebra.

Construct perpendiculars from each of these two lines.

The angle formed at their intersection represents the Segmental Lordosis Angle (°) for that specific segment.

The angle opens posteriorly, reflecting the normal lumbar lordotic curve.

For multi-level assessment, repeat for adjacent segments (e.g., L1–L5, L2–S1).

Record the measurement in degrees (°), noting the side of convexity if asymmetry exists.

3) Normal vs. Pathologic Ranges

L1-L5 Normal Range: ~40-50°; typical lumbar curvature

L4-S1 Normal Range: ~30-40°; primary contributor to lumbar lordosis

L5-S1 Normal Range: ~15-25°; segment with greatest individual lordosis

L3-L4 Normal Range: ~10-15°; moderate contribution to lordosis

L1-L3 Normal Range: ~5-10°; minimal segmental curvature

Pathologic Findings:

Hypolordosis: < normal segmental angles — flat back, disc degeneration, or instrumentation malalignment.

Hyperlordosis: > normal segmental angles — spondylolisthesis, compensatory changes, or facet hypertrophy.

Loss of distal lordosis (L4–S1) is particularly linked to positive sagittal imbalance and increased energy expenditure during stance.

4) Important References

Voutsinas SA, MacEwen GD. Sagittal profiles of the spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;(210):235–242.

Roussouly P, Gollogly S, Berthonnaud E, Dimnet J. Classification of the normal variation in the sagittal alignment of the human lumbar spine and pelvis in the standing position. Spine. 2005;30(3):346–353.

Le Huec JC, Aunoble S, Philippe L, Nicolas P. Pelvic parameters: origin and significance. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(Suppl 5):564–571.

Barrey C, Roussouly P, Perrin G, Le Huec JC. Sagittal balance disorders in severe degenerative spine: can we identify the compensatory mechanisms? Eur Spine J. 2011;20(Suppl 5):626–633.

Schwab F, Lafage V, Boyce R, Skalli W, Farcy JP. Gravity line analysis in adult volunteers: age-related correlation with spinal parameters, pelvic parameters, and foot position. Spine. 2006;31(25):E959–E967.

5) Other info....

Segmental Lordosis allows for targeted analysis of specific motion segments contributing to overall lumbar curvature.

In surgical planning, restoration of appropriate distal segmental lordosis (especially L4–S1) is critical for re-establishing physiologic sagittal balance.

The majority (~65%) of lumbar lordosis originates from the L4–S1 region; loss here has a disproportionate impact on global alignment.

Over- or under-correction during spinal fusion can cause flat-back deformity, adjacent segment disease, or sagittal decompensation.

EOS imaging or stitched long-cassette lateral radiographs are preferred for consistent, low-distortion measurement.

Always report both regional (L1–L5) and segmental (L4–S1) lordosis when evaluating lumbar reconstructive or degenerative conditions.