Image Type

Cobb Angle

1) Description of Measurement

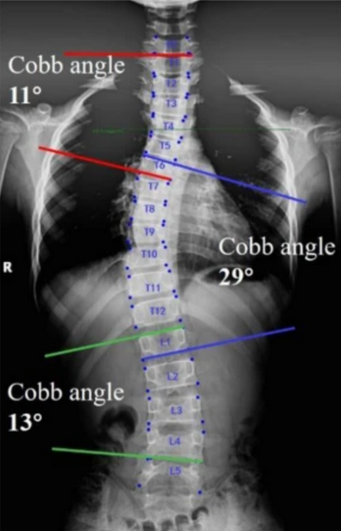

The Cobb Angle is the standard radiographic method for quantifying spinal curvature in scoliosis and assessing the severity of coronal plane deformity.

It measures the angle between the most tilted vertebrae at the upper and lower ends of a spinal curve, providing an objective estimate of curve magnitude.

Cobb angles are used to:

Diagnose scoliosis (≥ 10°)

Monitor curve progression over time

Guide decisions regarding bracing or surgical correction

While most commonly applied to thoracic and lumbar curves, the same technique is used in whole-spine images to evaluate global deformity and compensatory curves.

2) Instructions to Measure

Obtain a standing, full-length PA (or AP) spinal X-ray, ensuring visualization from C1 through the pelvis with the patient in neutral posture.

Identify the upper end vertebra (most tilted vertebra at the top of the curve) and the lower end vertebra (most tilted at the bottom).

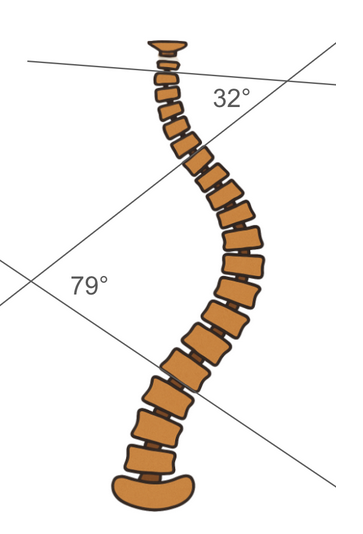

Draw a line along the superior endplate of the upper end vertebra and another along the inferior endplate of the lower end vertebra.

Construct perpendicular lines to each of these endplate lines.

Measure the angle formed at their intersection — this is the Cobb Angle.

If multiple curves exist (e.g., thoracic and lumbar), repeat the process for each curve.

The apical vertebra (the most laterally deviated vertebra) can be marked for reference.

For serial follow-up, always use the same vertebral levels and standardized patient positioning to ensure consistency.

3) Normal vs. Pathologic Ranges

Normal spinal alignment: Cobb angle < 10°; no structural scoliosis

Mild scoliosis: Cobb angle = 10-25°; observation and surveillance imaging indicated

Moderate scoliosis: Cobb angle = 25-45°; bracing often recommended (especially in skeletally immature patients)

Severe scoliosis: Cobb angle >45-50°; surgical correction typically indicated

Post operative goal: ≤10° residual curve; acceptable alignment post-correction

Key Points:

Scoliosis is defined as a Cobb angle ≥ 10° with associated vertebral rotation.

Curves should be documented as right- or left-convex based on their direction.

The measurement error can be ± 3–5°, so small differences between serial films may not indicate true progression.

4) Important References

Cobb JR. Outline for the study of scoliosis. In: Instructional Course Lectures. Vol 5. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1948:261–275.

Weinstein SL, Dolan LA, Wright JG, Dobbs MB. Effects of bracing in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(16):1512–1521.

Lenke LG, Betz RR, Harms J, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a new classification to determine extent of spinal arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(8):1169–1181.

Konieczny MR, Senyurt H, Krauspe R. Epidemiology of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Child Orthop. 2013;7(1):3–9.

Stokes IAF, Aronsson DD. Measurement of scoliosis: the importance of patient positioning and radiographic technique. Spine. 1992;17(4):425–429.

5) Other info....

Cobb Angle remains the gold standard for quantifying scoliosis on plain radiographs.

In double or triple curves, each curve’s Cobb angle should be measured and labeled (e.g., T4–T10 = primary thoracic; T11–L3 = lumbar compensatory).

EOS low-dose standing images or long-cassette X-rays are preferred for comprehensive spinal balance assessment.

Global alignment can also be assessed using additional parameters (e.g., coronal balance line, sagittal vertical axis, pelvic tilt).

Inter-observer variability is typically within ± 5°; use consistent landmarks and tools (manual goniometer or PACS software).

Cobb angle progression > 5° over serial exams indicates true curve progression and may alter treatment planning.